| Creating Space

for Dharma by Lama Thubten Yeshe |

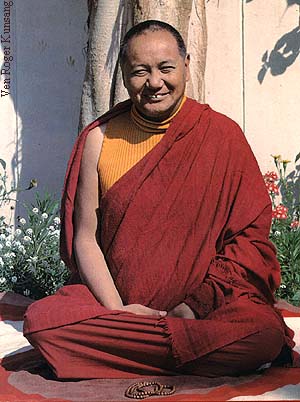

| Lama Thubten Yeshe was the spiritual leader of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, of which Tushita is a member. The following teaching demonstrates the dynamic, practical and psychologically-oriented approach that has brought him thousands of students the world over, and was given at Tushita on October 31st, 1979. |

Dharma philosophy is not Dharma; doctrine is not Dharma; religious art is not Dharma. Dharma is not that statue of Lord Buddha on your altar. Dharma, or religion, is the inner understanding of reality, which leads human beings beyond the dark shadow of ignorance, beyond dissatisfaction. It is not enough merely to accept Dharma as being true. We must also understand our individual reality, our specific needs, and the purpose of Dharma as it relates to us as individuals. If we accept Dharma for reasons of custom or culture alone, it does not become properly effective for our minds. For example, it would be wrong for me to think, "I'm a Tibetan, therefore I'm a mahayanist." Perhaps I can talk about mahayana philosophy, but to be a mahayanist, to have mahayana Dharma in my heart, is something else. We may be born into a dharmic country, into an environment where religion is accepted, but if we do not use that religion to gain an understanding of the reality of our own mind there is little sense in being a believer. Dharma cannot solve our problems if we do not approach it pragmatically. We should seek Dharma knowledge in order to stop our problems, to make ourselves spiritually healthy or, in religious terms, to discover eternal happiness, eternal peace, eternal bliss. We ourselves are responsible for discovering our own peace and liberation. We cannot say that some other power, like God, is responsible. Doing so is weak, for it means not accepting responsibility for the actions of our own body, speech and mind. A buddhist is responsible for all the actions that constitute his daily life: whether he directs them positively or negatively is in his own hands. So even though we find ourselves in a religious environment—in India, Tibet or even in the West—becoming religious is something else. External cultural aspects do not indicate the presence of Dharma. The purpose of Dharma is for us to lead ourselves beyond delusions, beyond the ego, beyond the usual human problems. If we use it in this way we can say, "I'm practising Dharma," but if we do not understand what Dharma really means there is little benefit in reciting even very powerful mantras. One of the most fundamental teachings of the Buddha is to renounce samsara. This does not mean that we should not drink water when thirsty. It means that we must understand samsara to the degree that even when we enter into a samsaric situation, no karmic reaction ensues. Application of skillful method and wisdom is the real renunciation; as long as there are grasping and hatred in our minds we have not renounced samsara. Perhaps we have changed our clothes and shaved off our hair, but if we ask ourselves, "What have I really renounced?" we may find our mind to be in exactly the same situation as it was before the external transformations. We have not stopped our problems. This is why samsara is called a cycle. It is cyclic existence. We do things: changing, changing, changing, changing. We enjoy the novelty of the change every time, but in fact all we are doing is creating more karma. Each time we create an action there is a reaction; a cycle that becomes ever tighter. That is samsara. To loosen this tightness we need wisdom able to eliminate the darkness of ignorance. It is not enough to think, "I am this religion," "Buddha will take care of me," "God will take care of me." Such beliefs are not enough. We must have some understanding of the reality of our own mind. Therefore Buddha taught numerous meditative techniques to wake us up from ignorance. At the beginning we must understand our needs as individuals; according to Lord Buddha's teachings each of us has different needs. Usually we ignore these and just accept whatever comes along without discriminating wisdom. As a result we end up on some kind of trip from which we cannot escape. That is samsara. Moreover, it is important for us to recognize that even if right now some of our ways and attitudes are wrong, there is the possibility that we can change and transform them. Grasping at permanence makes us think that we ourselves are unchanging. This negative thought-habit is very strong and prevents us from developing or acting in a dharmic way. Therefore Buddha taught the four noble truths. As a characteristic of the noble truth of suffering he taught impermanence. It is very important to know about impermanence. When we understand the impermanent nature of things, the non-stop change, we allow ourselves time and space to accept any situation that comes. Then, even if we are in a suffering situation we can take care of ourselves, we can look at it without getting upset. The upset or guilty mind prevents us from waking from confusion, from seeing our own clarity. Clarity always exists within us. The nature of our consciousness is clear. It is merely a question of seeing it. If we always feel we are dirty, negative, hopeless people who could never possibly discover inner peace and liberation, we are reacting to a deluded, negative mind, a fixed conception. We are thinking beyond reality, beyond the nature of phenomena. We have not touched reality. Such preconceived ideas have to be eradicated before tranquillity and peace can be cultivated, before we can touch reality with our intelligence. Check up right now. Ask yourself, "What am I?" "Who am I?" Even when we ask ourselves this on the relative plane we find that we are holding a permanent conception of the self of yesterday, the day before yesterday, last week, last month, and last year. This idea of the self is not correct. It is a preconception that must be broken down and recognized as unreasonable. Then we can understand the possibility of ceaseless, infinite development and spiritual growth. The beauty of human beings is that they can continuously develop inner qualities such as peace, the energy of the enlightenment experience, bliss— conceptions beyond our dualistic minds. When we understand this inner beauty we stop grasping at external materials, which can never give us eternal satisfaction. This is an important sign of spiritual progress. One cannot simultaneously be religious and grasp for material things; the two are incompatible. In this world we can see people becoming more confused and dissatisfied the more materials they get until finally they commit suicide. Sometimes poor people don't understand this; they think that the materially wealthy must be happy. They are not happy. They are dissatisfied, emotionally disturbed, confused and immersed in suffering. Suicide rates are higher in affluent than in economically undeveloped societies. This is not some Dharma philosophy—it is present-day reality; it applies to our twentieth century situation; it is happening right now. I am not suggesting that you people give up material comfort. Buddha never said that we have to give up our enjoyments; rather, he taught that we should never confuse ourselves by grasping at worldly pleasures. The underlying attitude that forces us to chase after unworthy objects is the delusion that causes us to think, "This object will give me satisfaction; without it life would be hopeless." These preconceptions render us incapable of dealing with the new situations that arise from day to day. We expect things to happen in a certain way so that when a different situation arises we are unable to react to it efficiently. Instead of handling the situation effectively we become tense, frustrated and psychologically disturbed. Dharma practice does not depend on cultural conditions. Whether we travel by car, train or plane we can still practise Dharma. However, in order to destroy the root of the dualistic mind completely, a partial understanding of the reality of our own mind is not sufficient. Dharma practice requires continued, penetrating development. Just a few flashes of understanding is not enough. To penetrate to that reality fully we must develop single-pointed concentration. Thus continuously the nature of our understanding will become indestructible. Most of us are emotionally unstable, sometimes up and sometimes down. When everything comes together as we want, we appear to be very religious; but when our situation becomes overwhelmingly bad, we lose our religious aspect. This is not good enough. It shows we that have no inner conviction, that our understanding of Dharma is very small and like a yo-yo. Some people may say, "I have been practising Dharma for ten years but still have many problems. I think Buddhism does not help." To them I am going to say, "Have you developed single-pointed concentration or penetrative insight?" This is the problem. Just saying, "Oh yes, I understand, I pray everyday, I am a good person" is not enough. That's why we say that Dharma is a total way of life. It is not just for breakfast, for Sunday, or for the temple. Maybe in a temple we are subdued and controlled, but outside we act quite differently. This indicates that our understanding of Dharma is not indestructible. Are we satisfied with our present states of consciousness? This is the logical reason why we need meditation, why we need Dharma. Worldly possessions do not give satisfaction. We cannot depend upon transitory objects for our happiness. For example, when we Tibetan refugees left Tibet we left behind our beautiful environment and way of life. Had my mind been so fixed that I believed my happiness and pleasure depended solely upon being in the place of my birth, I could never have been happy in India. I would think, "There are no snowy mountains here, I cannot be happy." The attitude of the mind is the trigger; physical problems are secondary. The way the human mind thinks is the real problem. Therefore we should avoid materialistic grasping and instead should search for an indestructible understanding of the ultimate reality of the mind. The Buddha's teaching on samadhi or meditative concentration is very important for it provides the power by which we can go beyond the conception of worldly thinking. However, having single-pointed concentration alone is not enough. We must unite it with vipashyana, or penetrative insight. What is the difference between these two? Firstly we develop single-pointed concentration, which leads us beyond worldly emotional problems and gives some higher satisfaction, but a certain degree of darkness still remains in the mind. In order to reach the deepest nature of human consciousness we also have to develop penetrative insight. This will lead us totally beyond the dualistic view of all existence. From the buddhist point of view it is this dualistic way of thinking that is the real conflict. We can attain some peace by means of meditative concentration, but if the dualistic view is in our minds there is still some conflict. The object of insight meditation, the experience of shunyata, is realization of non-duality. The flashing of the worldly sense objects and images disappears and there is the experience of the one total unity of absolute reality. Here there is a difference between the experience and the philosophy of shunyata. Philosophically, all the sense objects are existent, sense pleasure is existent and there is a relationship between the senses and the external world; but in the experience itself there is no awareness of a duality, no perception of the sense world, and no sense of conflict to irritate the mind. Normally, whenever we perceive the objects of the sense world we always see two things: we perceive the thing itself and immediately compare it with something else. Our society is built on this dualistic mind. Eventually it comes down to, if my next door neighbour gets a car I'm going to think that I also must get one. Two forces are at work, and one becomes the reason for the other. From the buddhist point of view any information received through the five sense consciousnesses is always distorted by dualistic grasping. It is like an optical illusion. It registers in our consciousness and we believe in it, yet it is merely an unreal distortion that gives birth to every delusion. Consequently the buddhist attitude towards data from the five sense consciousnesses is one of mistrust. We cannot rely on the judgements of good and bad that come through our senses. The senses always give a dualistic, distorted impression. The ordinary person would be better off if he went around with his eyes closed! We should always question and be critical of the information coming through our senses. In this way we can pass beyond normality, beyond the karmically-created actions and reactions of dissatisfaction.

Question: Are you saying that we are able to reach a state of full realization of shunyata? Answer: Definitely. How? By examining the nature of your own mind, repeatedly asking yourself, "What am I?" "Who am I?" Eventually we see the falseness of our instinctive ego-model and see how it projects itself into our life, causing us to misinterpret our every experience. When this wrong view is discovered we are close to an understanding of shunyata. Until we discover how ego-grasping is working within us, the understanding of shunyata is far away. Question: What is the relationship between shunyata and consciousness? Answer: Consciousness is not shunyata. But when we understand the nature of consciousness, the clarity of mind, we have an experience very similar to the experience of perceiving shunyata. Therefore in the Tibetan tradition of mahayana Buddhism we emphasize contemplating one's own consciousness as a preliminary leading to the absolute shunyata experience. Question: You spoke of sensory awareness disappearing in the experience of shunyata. How can one perceive the world without the five sensory consciousnesses? Answer: Well, there is both an absolute and a relative world. In the beginning one meditates on the nature of the relative world, and this then becomes the method by which the ultimate is discovered. The point is, one can look at the sensory world but should not be entranced by it. Be constantly analytical, checking up to see that your perception is clear and free from ego-based exaggeration. The relative reality is not a problem; the problem is that in our perception of things we exaggerate and distort the various aspects of an object. Therefore we must continually question our experience. We can't simply say, "It's right because I saw and wrong because I didn't." We have to go deeper than this.. Question: When you put a question to your mind, to whom do you put the question? Answer: When you question your own consciousness you question your wrong concept of believing in such a fallacious entity. When one sees a red glass one recognizes it as a red glass; but inside one doubts, "Maybe red, maybe white," constantly doubting. When you question, answers are forthcoming. Usually we just accept whatever occurs, never questioning. Consequently we are deluded and polluted. To question is to seek, and the answer lies within you. We feel that our consciousness is small, but it is like a mighty ocean in which everything can be found. When I talk you may think, "Maybe this lama will give me some realization," but there is no realization to give. To talk on Dharma is to throw switches here and there, hoping to wake people up. To believe in Buddha, Krishna or whomsoever is not enough; one must take responsibility for one's own body, speech and mind. We all have a certain degree of wisdom, and this must be cultivated. All religions use bells—Tibetan and hindu included. The bell symbolizes wisdom. This bell of wisdom is lying unused within all of us. Ringing the ritual bell is a reminder for us: "Use your wisdom!" Question: Admittedly we should not be overly passive in our responsibilities, but sometimes taking karmic responsibility seems to heighten the sense of ego. There seems to be a choice between responsibility and outward energy as opposed to passive, inner wisdom. Answer: Intellectually we understand that there is Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. This is positive; and Buddha is okay, Dharma is okay, Sangha is okay. But what is Buddha to me? When I totally develop myself, I am buddha. That is my buddha. Shakyamuni Buddha is his buddha, not mine. He has gone. My total awakening is my buddha. How to wake up to your own buddha? Simply by being aware of your own actions of body, speech and mind is the beginning. Of course you should not be egotistical about it, thinking, "Buddha and Dharma are okay, but I don't care about them—I am responsible." And also you should not have pride: "I am a meditator." The whole point is to eradicate the ego—don't worry about whether you are a meditator or not. Just put your mind in the right channel, don't intellectualize, and let it go. Yours is a very good question: we have to know how to deal with that mind. Thank you. Question: You said that suicide rates are higher in the West than in the East. But it is also true that death from starvation is commoner in the East than in the West. It seems to be instinctive for the Easterner to renounce, whereas materialism appears natural for Westerners, so may I suggest, skeptically, that renunciation has led the East to poverty and materialism the West to affluence? Answer: That is also a very good question. But remember what I said before? Renouncing this glass does not mean throwing it away, breaking it or giving it to someone else. We can eat our rice and dal with a renounced mind. This we have to learn. It is true that most Eastern people are culturally influenced by their religious tenets. For example, even when we are three or four years old we accept the law of karma. But then most followers of Eastern religions also misunderstand karma. One might think, "Oh, I'm a poor person, my father is a sweeper—I too have to be a sweeper." Someone asks him why. "Because it is my karma—it has to be that way." This is a total misconception having nothing to do with the teachings of either the hindu or the buddhist religions—a fixed idea contrary to the nature of reality. We should understand, "I'm a human being—my nature is impermanent. Maybe I'm unhappy now, but I'm changeable—within myself I can develop the mind of eternal peace and joy." This is the attitude we should have. The incredible changes in the world today come from the human mind, not from the world itself; the affluence of the materialistic West comes from the Western mind. So if we Eastern people want to change our standards of living for those of the West we can do it. Yet at the same time we can have renunciation of samsara. We must understand the real value of material goods and their relationship to happiness in order to develop renunciation. Most Westerners grossly exaggerate the value of materials. They are bombarded with advertisements: "This (object) gives you satisfaction," "This gives you satisfaction," "This gives you satisfaction." So they become psychologically convinced, "I must buy this, I must buy that, otherwise I won't be happy." This conviction leads them to the extreme of materialism—and ultimately to suicide. Similarly, Easterners misconceive the teachings of religion and fall into the extreme of passivity, laziness and apathy: "Karma—it's my karma." Question: What is the difference between moksa and nirvana? Answer: There are several levels of moksa or liberation. One of these is nirvana, which is beyond ego and is endowed with peace and bliss. Higher than nirvana is the enlightenment that is the fruition of bodhicitta, the enlightened aspiration to achieve buddhahood in order to benefit all the infinite beings. Someone may lose interest in samsara, undergo spiritual training and gain nirvana, but he has yet to develop the bodhicitta and realize full enlightenment. Question: You spoke about non-duality: in that state are there no love and hate? Answer: I think that the experience of non-duality itself has the nature of love. The emotional tone of love is lower during meditative absorption on non-duality, but the nature of love is essentially present. Most people live a dualistic, biased love. A love characterized by non-duality feels no partialities. In the lam.rim we are taught to meditate on how every single being has repeatedly been a mother to us in previous lives. All beings, including animals, birds, fish and insects, have similarly been a mother to us. Moreover, without exception they all want happiness and seek to avoid suffering. If we meditate and expand our subjects of knowledge, the nature of the beings becomes known and one's love becomes vast. Question: Nirvana seems to be a duality because it implies non-nirvana. Answer: This is linguistically true. If we give the label "nirvana, " we create an entrance for the label "non-nirvana." But in the mind of someone perceiving non-duality there is no such label. He just experiences nirvana and lets himself go into it. Question: I always visualize nirvana as the LSD experience. Answer: Then I suppose we don't have much nirvana, here in the East. |

| Lama Thubten

Yeshe was the founder of the FPMT. This teaching, which was given at

Tushita on October 31st, 1979, demonstrates the dynamic, practical and

psychologically oriented approach that brought him thousands of students

the world over and is imbued with the bodhicitta that characterized Lama's

entire being.

From Teachings at Tushita, edited by Nicholas Ribush with Glenn H. Mullin, Mahayana Publications, New Delhi, 1981. A new edition of this book is in preparation. Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre is the FPMT centre in New Delhi, India. |

The Organization

Teachers | Teachings | Education

FPMT Centers | Links | Search